The Eule Organ of Magdalen College, Oxford – Review by Fanfare Magazine

"What a treat this release is: Pott is a superb organist... the Eule organ is clearly an instrument both imposing and lovely, caught in a fabulous recording. Absolutely recommended; one of Convivium’s finest releases."

23rd September 2025

The Eule Organ of Magdalen College, Oxford – Review by Fanfare Magazine

"What a treat this release is: Pott is a superb organist... the Eule organ is clearly an instrument both imposing and lovely, caught in a fabulous recording. Absolutely recommended; one of Convivium’s finest releases."

23rd September 2025

Listen or buy this album:

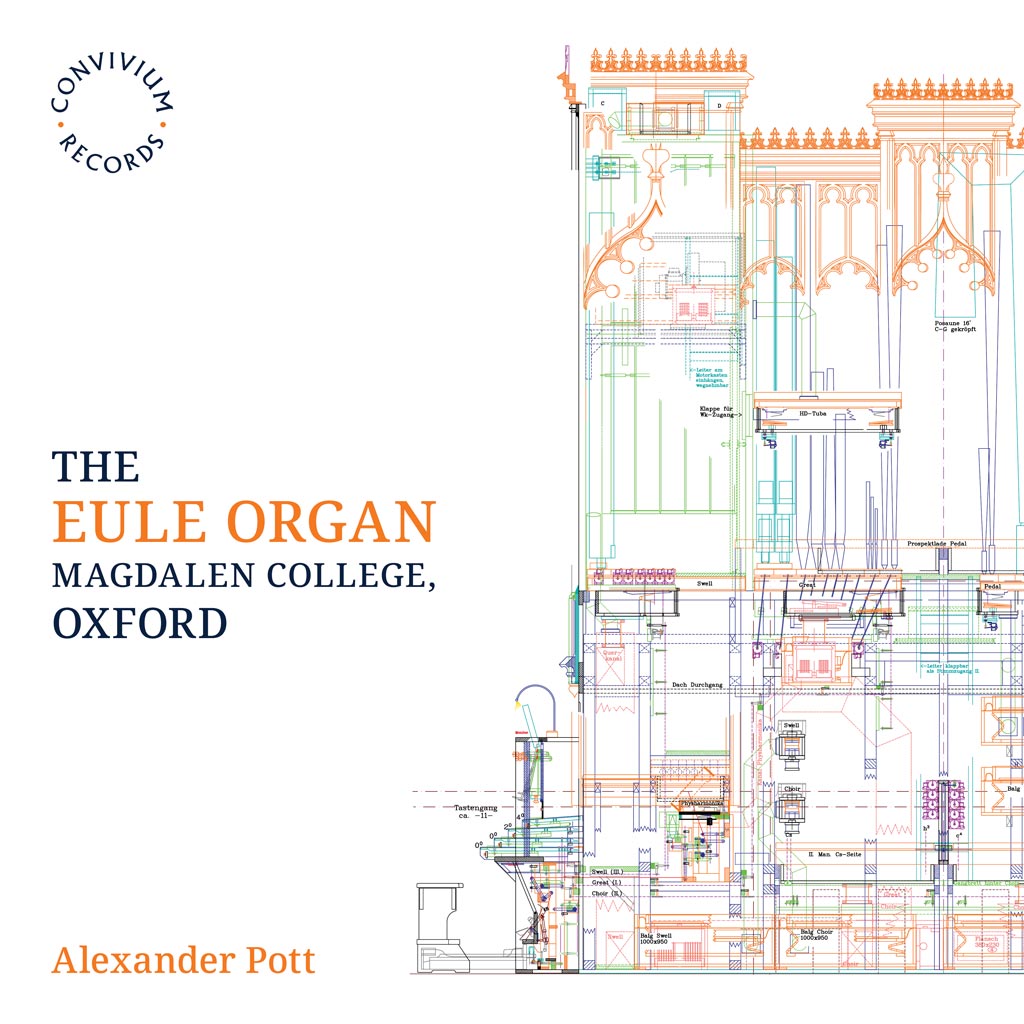

This 88-minute release celebrates the new organ at Magdalen College, University of Oxford, unveiled in January 2023. Although there is a Germanic heritage to the instrument (more than adequately acknowledged here), the program also includes a number of English gems, not least via Ethel Smyth and Frederic Austen (more soon!). The booklet note, “Anglo-Saxony: A Leipzig Legacy” explains the organ was designed and built in Saxony, then installed at Magdalen. And many of the great composers have interacted with either, or both, Leipzig and Dresden. It is a fascinating premise, or, if you will, launching point for this recital. Also in Saxony is Bautzen, a small town near the borders with Poland and the Czech Republic (as it is today). It was also the hometown of Hermann Eule, an organ builder, whose first instrument landed in Dresden in 1878 and Leipzig in 1894.

The recital begins in quite a hefty way, with Liszt’s Funérailles in an arrangement by Jeanne Demessieux (1921–68, from 1962 organist at La Madeleine in Paris; she studied organ with Marcel Dupré and piano with Magda Tagliaferro). Demessieux’s transcription of Funérailles appears to have gone unpublished until 2010, so it is good to have it here. A number of the pieces appear in review on the Fanfare Archive; I can feel a massive listing detour coming on when I listen to this transcription. It is masterly, so inventive, so beautiful, and Alexander Pott seems to realize where each and every nuance lies. The organ and this recording seem to deliver so much detail: there is no blurring at the big tune around eight minutes in, for example. Pott delivers so much excitement thereafter (although it is difficult to get the sound of a piano out of one’s ear as the obsessive bass bell repetitions accrue). Yes, this piece sounds very, very Gothic on the organ, but this is so much more than a curio. Demessieux, as we have seen no ingenue on the piano, surely set out to bring out different aspects of the piece. If so, she certainly succeeded. Pott’s performance is stunning, and exhausting to listen to (and so it should be). Few recitals begin as auspiciously as this.

While the organ sounds stunning in the Wagner/Liszt Tannäuser Overture, Pott takes the opening unaccountably slowly. It loses momentum, any sense of devotion dissipated. Things do improve as the score gets busier, but the return of the opening (around five minutes in) finds the music again running out of steam; a hesitation (agogic accent is the intent, I presume) before a significant chord implies the music might actually stop. This feels like the exception in this release and is certainly not enough to preclude a recommendation overall.

After interviewing Martin Anderson of Toccata Classics and his related labels recently, it came as a surprise to see that a review of Reinecke’s Organ Sonata in G Minor, op. 284 on that label is not in the Fanfare Archive. It is a fine performance by Jan Lehtola. Including Reinecke after Liszt makes sense on the present disc, as Reinecke studied with the Master. From 1860 to 1895, Reinecke conduced the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, which “places” him nicely for present purposes. This is a late work. The first movement uses material from the chorale Wie schön leuchet der Morgenstern. Both Lehtola (at the Walcher organ in the Johanneskirkko, Helsinki) and Pott are well recorded, with the new Oxford release pipping Toccata at the post; also, I find Pott has more of a sense of flow. Convivium tracks this as one, whereas Toccata tracks each movement (both have validity: it is played as a continuous whole and there are bridging passages between each section: obviously, reviewers prefer the segmentation!). The Lento (which begins at 5:07 in the Convivium) moves nicely in Pott’s account, with lovely contrasts. I do find Pott more mysterious in this movement than Lehtola, and he attains a lovely sense of contained majesty. The finale (9:32 in Pott’s account) bursts through in the Convivium performance with almost carillon joy; the subsequent overshadowing is effective, therefore, while the choice of stop for the cantus firmus is certainly arresting (Lehtola sounds restrained in comparison). This is a close one to call, and context will account for much; in the final analysis, for me at least, Pott just pips Lehtola.

It is so good to see Dame Ethel here. Her Prelude and Fugue on “O Traurigkeit, O Herzeleid” kicks off the second disc. Smyth studied with Reinecke for a short time (it was not a happy time, though), which continues the web of connections. Her Prelude and Fugue on “O Truigkeit, O Herzeleid” presents the chorale nicely in the Prelude before embarking on thematic exploration via fugue. It is a terrific piece, beautifully cogent. The recording by Susan Ferré on Gothic is more present, her choice of stop almost acidic for the Prelude, though, and some of her playing labored in comparison to Pott. On her disc Preludes & Postludes, Ferré also includes some Karg-Elert (who studied at the Leipzig Conservatory); so does Pott, Karg-Elert’s “The Reed-Grown Waters” (from Seven Pastels from the Lake of Constance). This is a harmonically elusive piece, very enigmatic, and also quite gestural at times. There is, incidentally, a rather charming “cuckoo” too, nicely bought out by Pott. I agree with Martin Anderson in his review in Fanfare 25:6 that Hans Fagius on Bis is superb (on the organ of Aarhus Cathedral, Denmark), but I find Pott just a touch more involving.

Delius can be quite soporific. Depending on your viewpoint, that is either a massive overgeneralization (yes, I know, Sleigh Ride) or core truth. There is a rather nice link between the cuckoo in the Karg-Elert and the one in Delius, though, which I suspect played a great part in this piece’s inclusion (as did the fact Delius attended the Leipzig Conservatory and studied with Reinecke). It is a short piece, heard here in Eric Fenby’s arrangement; a rather nice timbal opening out alleviates any perceived longueurs, and Pott keeps it, thankfully, moving.

Percy Whitlock wrote his Four Extemporizations in 1932–3. No. 4 is by far the most recorded (“Fanfare”) with No. 3 making an occasional appearance (“Fidelis”: John Winter recorded Nos. 3 and 4 together for Priory). Sadly, I have not heard Jennifer Bate’s recording of all four (it was on the now defunct ASV, which accounts for it: Fanfare 23:2, 1999). In his review of that Bate, Martin Anderson referred to Whitlock’s music as “unassuming” and I agree; it is lovely in a very English way, though, and I like Pott’s restrained interpretation.

Percy Grainger’s The Immovable Do (that’s “Doh” the note), humorously ribbing stuck organ notes, comes across nicely here while including some grandeur. It is nice to have Warlock’s 1918 Folk-Song Preludes here in Pott’s own arrangement, five short pieces that were that composer’s only work for piano (Paul Guiney has recorded a creditable account, if not in the best sound, for Stone Records). Frankly, the second sounds far more at home on a piano; Pott introduces some interesting effects, but here it is Guiney that triumphs. If there is one instrument that can do “Maestoso,” though, it is the organ, and so the third is a success, even if some of the harmonies do blur. The fourth, though, works better on organ (at least against Guiney’s account). Marked with a nebulous “fairly slow” indicator, it is something of a processional; the fifth is a Largo maestoso, losing some of its folkish basis in the transfer over to organ, sadly. A pity the last movement works the least well in its hoisting over to the organ loft, but it’s good to see this music here.

It looks as though Frederic Austin lived a fascinating life (see Bary Berensal’s overview in Fanfare 36:2). Bax and Addinsell are referenced in various reviews of his work, so yes, think English music, and indeed English film music, of the 1930s or 1940s. If you want a taste of his output, try Rumon Gamba’s recording of The Sea Venturers (1935) on Chandos, with the BBC Philharmonic. Rather tidily, Austin’s Organ Sonata in G Minor is dedicated to Whitlock. It opens absolutely in the spirit of Walton’s Crown Imperial, and this passage returns several times separated by quieter dancelike sections. The sonata received its modern premiere in 2022 by Charles Matthews, and this is its first recording. It is a fabulous work, cleanly composed and cleanly performed here by Pott. It also shows the Eule organ to its very best, and not inconsiderable, advantage.

What a treat this release is: Pott is a superb organist (is it a compliment to say you can’t tell he is an academic from his playing?) and the Eule organ is clearly an instrument both imposing and lovely, caught in a fabulous recording (it was produced by Geoge Richford and engineered by Adaq Khan). Absolutely recommended; one of Convivium’s finest releases.

Review written by:

Review published in:

Other reviews by this author:

This 88-minute release celebrates the new organ at Magdalen College, University of Oxford, unveiled in January 2023. Although there is a Germanic heritage to the instrument (more than adequately acknowledged here), the program also includes a number of English gems, not least via Ethel Smyth and Frederic Austen (more soon!). The booklet note, “Anglo-Saxony: A Leipzig Legacy” explains the organ was designed and built in Saxony, then installed at Magdalen. And many of the great composers have interacted with either, or both, Leipzig and Dresden. It is a fascinating premise, or, if you will, launching point for this recital. Also in Saxony is Bautzen, a small town near the borders with Poland and the Czech Republic (as it is today). It was also the hometown of Hermann Eule, an organ builder, whose first instrument landed in Dresden in 1878 and Leipzig in 1894.

The recital begins in quite a hefty way, with Liszt’s Funérailles in an arrangement by Jeanne Demessieux (1921–68, from 1962 organist at La Madeleine in Paris; she studied organ with Marcel Dupré and piano with Magda Tagliaferro). Demessieux’s transcription of Funérailles appears to have gone unpublished until 2010, so it is good to have it here. A number of the pieces appear in review on the Fanfare Archive; I can feel a massive listing detour coming on when I listen to this transcription. It is masterly, so inventive, so beautiful, and Alexander Pott seems to realize where each and every nuance lies. The organ and this recording seem to deliver so much detail: there is no blurring at the big tune around eight minutes in, for example. Pott delivers so much excitement thereafter (although it is difficult to get the sound of a piano out of one’s ear as the obsessive bass bell repetitions accrue). Yes, this piece sounds very, very Gothic on the organ, but this is so much more than a curio. Demessieux, as we have seen no ingenue on the piano, surely set out to bring out different aspects of the piece. If so, she certainly succeeded. Pott’s performance is stunning, and exhausting to listen to (and so it should be). Few recitals begin as auspiciously as this.

While the organ sounds stunning in the Wagner/Liszt Tannäuser Overture, Pott takes the opening unaccountably slowly. It loses momentum, any sense of devotion dissipated. Things do improve as the score gets busier, but the return of the opening (around five minutes in) finds the music again running out of steam; a hesitation (agogic accent is the intent, I presume) before a significant chord implies the music might actually stop. This feels like the exception in this release and is certainly not enough to preclude a recommendation overall.

After interviewing Martin Anderson of Toccata Classics and his related labels recently, it came as a surprise to see that a review of Reinecke’s Organ Sonata in G Minor, op. 284 on that label is not in the Fanfare Archive. It is a fine performance by Jan Lehtola. Including Reinecke after Liszt makes sense on the present disc, as Reinecke studied with the Master. From 1860 to 1895, Reinecke conduced the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, which “places” him nicely for present purposes. This is a late work. The first movement uses material from the chorale Wie schön leuchet der Morgenstern. Both Lehtola (at the Walcher organ in the Johanneskirkko, Helsinki) and Pott are well recorded, with the new Oxford release pipping Toccata at the post; also, I find Pott has more of a sense of flow. Convivium tracks this as one, whereas Toccata tracks each movement (both have validity: it is played as a continuous whole and there are bridging passages between each section: obviously, reviewers prefer the segmentation!). The Lento (which begins at 5:07 in the Convivium) moves nicely in Pott’s account, with lovely contrasts. I do find Pott more mysterious in this movement than Lehtola, and he attains a lovely sense of contained majesty. The finale (9:32 in Pott’s account) bursts through in the Convivium performance with almost carillon joy; the subsequent overshadowing is effective, therefore, while the choice of stop for the cantus firmus is certainly arresting (Lehtola sounds restrained in comparison). This is a close one to call, and context will account for much; in the final analysis, for me at least, Pott just pips Lehtola.

It is so good to see Dame Ethel here. Her Prelude and Fugue on “O Traurigkeit, O Herzeleid” kicks off the second disc. Smyth studied with Reinecke for a short time (it was not a happy time, though), which continues the web of connections. Her Prelude and Fugue on “O Truigkeit, O Herzeleid” presents the chorale nicely in the Prelude before embarking on thematic exploration via fugue. It is a terrific piece, beautifully cogent. The recording by Susan Ferré on Gothic is more present, her choice of stop almost acidic for the Prelude, though, and some of her playing labored in comparison to Pott. On her disc Preludes & Postludes, Ferré also includes some Karg-Elert (who studied at the Leipzig Conservatory); so does Pott, Karg-Elert’s “The Reed-Grown Waters” (from Seven Pastels from the Lake of Constance). This is a harmonically elusive piece, very enigmatic, and also quite gestural at times. There is, incidentally, a rather charming “cuckoo” too, nicely bought out by Pott. I agree with Martin Anderson in his review in Fanfare 25:6 that Hans Fagius on Bis is superb (on the organ of Aarhus Cathedral, Denmark), but I find Pott just a touch more involving.

Delius can be quite soporific. Depending on your viewpoint, that is either a massive overgeneralization (yes, I know, Sleigh Ride) or core truth. There is a rather nice link between the cuckoo in the Karg-Elert and the one in Delius, though, which I suspect played a great part in this piece’s inclusion (as did the fact Delius attended the Leipzig Conservatory and studied with Reinecke). It is a short piece, heard here in Eric Fenby’s arrangement; a rather nice timbal opening out alleviates any perceived longueurs, and Pott keeps it, thankfully, moving.

Percy Whitlock wrote his Four Extemporizations in 1932–3. No. 4 is by far the most recorded (“Fanfare”) with No. 3 making an occasional appearance (“Fidelis”: John Winter recorded Nos. 3 and 4 together for Priory). Sadly, I have not heard Jennifer Bate’s recording of all four (it was on the now defunct ASV, which accounts for it: Fanfare 23:2, 1999). In his review of that Bate, Martin Anderson referred to Whitlock’s music as “unassuming” and I agree; it is lovely in a very English way, though, and I like Pott’s restrained interpretation.

Percy Grainger’s The Immovable Do (that’s “Doh” the note), humorously ribbing stuck organ notes, comes across nicely here while including some grandeur. It is nice to have Warlock’s 1918 Folk-Song Preludes here in Pott’s own arrangement, five short pieces that were that composer’s only work for piano (Paul Guiney has recorded a creditable account, if not in the best sound, for Stone Records). Frankly, the second sounds far more at home on a piano; Pott introduces some interesting effects, but here it is Guiney that triumphs. If there is one instrument that can do “Maestoso,” though, it is the organ, and so the third is a success, even if some of the harmonies do blur. The fourth, though, works better on organ (at least against Guiney’s account). Marked with a nebulous “fairly slow” indicator, it is something of a processional; the fifth is a Largo maestoso, losing some of its folkish basis in the transfer over to organ, sadly. A pity the last movement works the least well in its hoisting over to the organ loft, but it’s good to see this music here.

It looks as though Frederic Austin lived a fascinating life (see Bary Berensal’s overview in Fanfare 36:2). Bax and Addinsell are referenced in various reviews of his work, so yes, think English music, and indeed English film music, of the 1930s or 1940s. If you want a taste of his output, try Rumon Gamba’s recording of The Sea Venturers (1935) on Chandos, with the BBC Philharmonic. Rather tidily, Austin’s Organ Sonata in G Minor is dedicated to Whitlock. It opens absolutely in the spirit of Walton’s Crown Imperial, and this passage returns several times separated by quieter dancelike sections. The sonata received its modern premiere in 2022 by Charles Matthews, and this is its first recording. It is a fabulous work, cleanly composed and cleanly performed here by Pott. It also shows the Eule organ to its very best, and not inconsiderable, advantage.

What a treat this release is: Pott is a superb organist (is it a compliment to say you can’t tell he is an academic from his playing?) and the Eule organ is clearly an instrument both imposing and lovely, caught in a fabulous recording (it was produced by Geoge Richford and engineered by Adaq Khan). Absolutely recommended; one of Convivium’s finest releases.