The Eule Organ of Magdalen College, Oxford – Review by Laudate Magazine

"Congratulations to Convivium Records for engaging in this most fascinating project... The choice of music is enterprising, and the performances excellent."

27th January 2026

The Eule Organ of Magdalen College, Oxford – Review by Laudate Magazine

"Congratulations to Convivium Records for engaging in this most fascinating project... The choice of music is enterprising, and the performances excellent."

27th January 2026

Listen or buy this album:

Congratulations to Convivium Records for engaging in this most fascinating project: the first recording of the new Magdalen College organ (2023). The organ was built by Eule Orgelbau of Bautzen Germany, whose website https://www.euleorgelbau.de/en/home is a must for organ devotees. Incidentally, it is probably fairly widely known that the City of London church of St Bartholomew the Great is also to acquire a new organ from Eule (https://www.greatstbarts. com/organ)

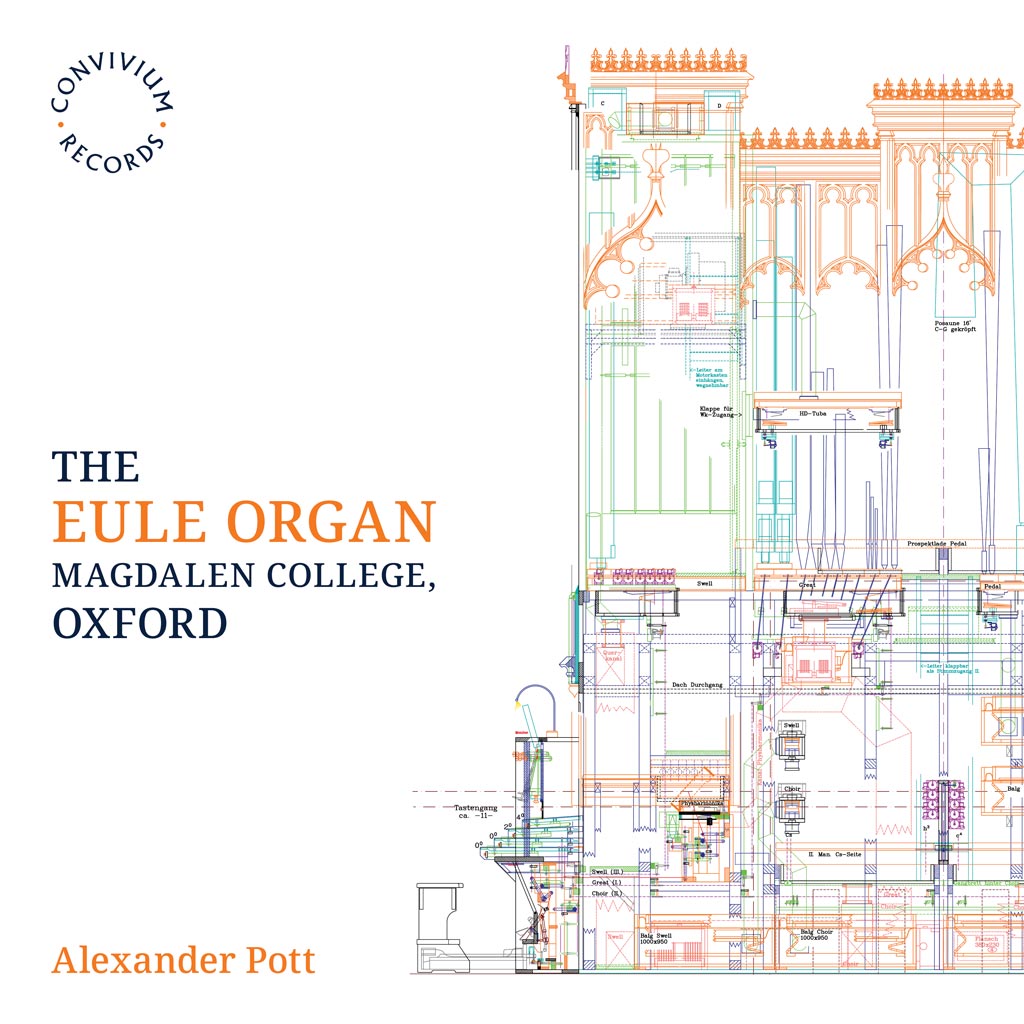

The choice of music on CR109 is enterprising, and the performances excellent. I strongly commend also Alexander Pott’s programme note ‘Anglo-Saxony: A Leipzig Legacy’, and the page entitled ‘The Eule Organ’. In the latter we read how Mark Williams, the Informator Choristarum at Magdalen, seized the ‘opportunity to…creat[e] an organ that would have a distinct voice and meet the musical demands of daily Anglican choral services in the chapel’. In addition to this latter and most vital requirement, the organ, as demonstrated on CR109, enables performance of an extensive solo repertoire. Its four-manual-and-pedal specification is shown, and we are also given a couple of original construction drawings of the console and the stop jambs (although the reproduction of these is perforce rather small for visual comfort).

Pott has chosen repertoire from ‘German Romanticism to 20th Century English composers – two styles that demonstrate the new Eule organ…at its most colourful best’. The programme as a whole – which spreads over two discs, the first of about 38 minutes, the second of about 50 – ‘gives an opportunity to tell a story of musical influence that includes some more unusual names amongst the well-known ones, and embraces the art of transcription as a way to present a fresh narrative’.

Accordingly the earliest composers represented are Wagner, Liszt, and Carl Reinecke (1824–1910) – while the more recent include Percy Grainger (1882–1961) and Frederick Austin (1872–1952). Clearly therefore – and this is no complaint – we hear nothing by, for example, J.S. Bach or other pre-19th century Germans, by French composers, or by composers alive today. Perhaps some future recording might show what the organ can do with Baroque music and some later styles, including French (the Récit does have ‘heavier French-style sounds’ than the Swell with its ‘softer, German-style division’).

CD 1 has three items. The first is Liszt’s ‘Funérailles’ from Harmonies poétiques et religieuses. This piece, originally for piano, was transcribed for organ by the celebrated organ virtuoso and composer Jeanne Demessieux (1931–68). The title is perhaps a little forbidding for an opening item, but the dramatic character of the work fully engages the listener, both in terms of musical content and the range of organ sonorities. For Liszt this piece was intensely personal: we are told that he had lost friends in the repression associated with the failed Hungarian Revolution of 1848, the year before ‘Funérailles’ was composed. The second piece on CD 1 follows on neatly as another Liszt transcription, for organ, of Wagner’s ‘Pilgrims’ chorus from Tannhäuser.

CD 1 concludes with a sonata by Carl Reinecke, to represent the less ‘progressive’ side of composition in the second half of the 19th century, in which Mendelssohn, Schumann and Brahms rather than Wagner and Liszt were principal figures. Reinecke’s late Sonata in G minor (1909), an organ work from the beginning, not a transcription, is his Op. 284. Op. 284! Reinecke was certainly prolific! It may not leave a strong impression on the listener, but is certainly competent and well-crafted. Pott is not the first to record it, Jan Lehtola having done so for Toccata (TOCC0505, 2019).

One of those who were distinctly unenthusiastic about Reinecke was Ethel Smyth (1858–1944), briefly one of Reinecke’s pupils. CD 2 begins with her fine Prelude and Fugue on ‘O Traurigkeit, O Herzeleid’ (composed in the early 1880s). There are echoes of J.S. Bach here, and the work apparently dates from her student years in Germany.

There is much of interest on the rest of CD 2. Alexander Pott’s excellent notes will explain the nature of the ‘journey’ traced. Suffice it here to pick out three items that have made a particular impression on me. (The others are Karg-Elert’s ‘The Reed-grown Waters’ (Op. 86 No. 4); Percy Whitlock’s ‘Carol’ (Four Extemporisations, No. 1); and Organ Sonata in G major by Frederick Austin, recorded here for the first time.)

First, I choose the atmospheric tone poem On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring (1912) by Frederick Delius – another pupil of Reinecke. It appears here in the wonderfully serene arrangement for organ (1934) by Eric Fenby, who was Delius’s amanuensis from 1928 to 1934, and an organist from an early age.

Alexander Pott himself arranged Peter Warlock’s Folk Song Preludes of 1918, a set of five delightful miniatures. His notes identify the folk songs employed, except that the first has not been identified. My guess is that it is Scottish, like Nos 2, 3 and 5. The fourth embodies a Welsh tune; Warlock had strong connections with Wales, and learned the language. Pott refers to something that I had noticed independently: that Warlock’s characteristically whimsical direction to the pianist to make a crescendo and a diminuendo on the penultimate chord (bar 16) is something actually achievable on the organ!

My third choice is ‘The Immovable Do’ by Percy Grainger. (Grainger, like Warlock, was a friend of Delius, whose music and that of his circle is of great interest and importance to Pott ‘as a researcher on Delius’.) ‘Do’, the first note in the tonic solfa series can be movable, in that it will be the tonic in whatever key is in use. Its immobility in Grainger’s piece is explained by the subtitle ‘The Cyphering C’: the top C sounds throughout the piece, having been ‘wedged down with a pencil’ to imitate the familiar organ fault of a note getting stuck and persisting when not needed.

What does the composer do when incorporating a simulated cypher? He or she can employ harmonies that accord with the perpetual C, with minor licences, perhaps – as Purcell did in his ‘Fantazia on One Note, with its internal pedal-note F. Noel Rawsthorne (1929–2019), whose charming ‘Prière’ for organ has top C similarly wedged down throughout, is also generally ‘law-abiding’. Grainger, in a piece lasting 5’38”, is, as we might expect, harmonically more adventurous from time to time, although the basic F major tonality is emphasised. Grainger’s F major (like Rawsthorne’s) in fact means that the held C is the dominant (‘so’), rather than ‘do’. This is no doubt because overall the harmony is easier to manage this way (in C major there would be too many B-against-C clashes probably; in F a V–I progression will be entirely consonant).

Grainger’s piece is published, and an edition (from Schirmer) may be viewed in the online Petrucci Music Library. There is an extensive note there from the composer, explaining that the work was conceived in 1933, but not ‘written out’ for organ until 1941, although it was originally thought of as ‘for organ (or harmonium) or voices, or both together (with possible association of strings and wind groups, or orchestra, or band)’. Typical Grainger touches are the sometimes idiosyncratic English performance directions, including the opening ‘Stridingly’ – and the dedication ‘For my merry wife’.

Review written by:

Review published in:

Other reviews by this author:

Congratulations to Convivium Records for engaging in this most fascinating project: the first recording of the new Magdalen College organ (2023). The organ was built by Eule Orgelbau of Bautzen Germany, whose website https://www.euleorgelbau.de/en/home is a must for organ devotees. Incidentally, it is probably fairly widely known that the City of London church of St Bartholomew the Great is also to acquire a new organ from Eule (https://www.greatstbarts. com/organ)

The choice of music on CR109 is enterprising, and the performances excellent. I strongly commend also Alexander Pott’s programme note ‘Anglo-Saxony: A Leipzig Legacy’, and the page entitled ‘The Eule Organ’. In the latter we read how Mark Williams, the Informator Choristarum at Magdalen, seized the ‘opportunity to…creat[e] an organ that would have a distinct voice and meet the musical demands of daily Anglican choral services in the chapel’. In addition to this latter and most vital requirement, the organ, as demonstrated on CR109, enables performance of an extensive solo repertoire. Its four-manual-and-pedal specification is shown, and we are also given a couple of original construction drawings of the console and the stop jambs (although the reproduction of these is perforce rather small for visual comfort).

Pott has chosen repertoire from ‘German Romanticism to 20th Century English composers – two styles that demonstrate the new Eule organ…at its most colourful best’. The programme as a whole – which spreads over two discs, the first of about 38 minutes, the second of about 50 – ‘gives an opportunity to tell a story of musical influence that includes some more unusual names amongst the well-known ones, and embraces the art of transcription as a way to present a fresh narrative’.

Accordingly the earliest composers represented are Wagner, Liszt, and Carl Reinecke (1824–1910) – while the more recent include Percy Grainger (1882–1961) and Frederick Austin (1872–1952). Clearly therefore – and this is no complaint – we hear nothing by, for example, J.S. Bach or other pre-19th century Germans, by French composers, or by composers alive today. Perhaps some future recording might show what the organ can do with Baroque music and some later styles, including French (the Récit does have ‘heavier French-style sounds’ than the Swell with its ‘softer, German-style division’).

CD 1 has three items. The first is Liszt’s ‘Funérailles’ from Harmonies poétiques et religieuses. This piece, originally for piano, was transcribed for organ by the celebrated organ virtuoso and composer Jeanne Demessieux (1931–68). The title is perhaps a little forbidding for an opening item, but the dramatic character of the work fully engages the listener, both in terms of musical content and the range of organ sonorities. For Liszt this piece was intensely personal: we are told that he had lost friends in the repression associated with the failed Hungarian Revolution of 1848, the year before ‘Funérailles’ was composed. The second piece on CD 1 follows on neatly as another Liszt transcription, for organ, of Wagner’s ‘Pilgrims’ chorus from Tannhäuser.

CD 1 concludes with a sonata by Carl Reinecke, to represent the less ‘progressive’ side of composition in the second half of the 19th century, in which Mendelssohn, Schumann and Brahms rather than Wagner and Liszt were principal figures. Reinecke’s late Sonata in G minor (1909), an organ work from the beginning, not a transcription, is his Op. 284. Op. 284! Reinecke was certainly prolific! It may not leave a strong impression on the listener, but is certainly competent and well-crafted. Pott is not the first to record it, Jan Lehtola having done so for Toccata (TOCC0505, 2019).

One of those who were distinctly unenthusiastic about Reinecke was Ethel Smyth (1858–1944), briefly one of Reinecke’s pupils. CD 2 begins with her fine Prelude and Fugue on ‘O Traurigkeit, O Herzeleid’ (composed in the early 1880s). There are echoes of J.S. Bach here, and the work apparently dates from her student years in Germany.

There is much of interest on the rest of CD 2. Alexander Pott’s excellent notes will explain the nature of the ‘journey’ traced. Suffice it here to pick out three items that have made a particular impression on me. (The others are Karg-Elert’s ‘The Reed-grown Waters’ (Op. 86 No. 4); Percy Whitlock’s ‘Carol’ (Four Extemporisations, No. 1); and Organ Sonata in G major by Frederick Austin, recorded here for the first time.)

First, I choose the atmospheric tone poem On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring (1912) by Frederick Delius – another pupil of Reinecke. It appears here in the wonderfully serene arrangement for organ (1934) by Eric Fenby, who was Delius’s amanuensis from 1928 to 1934, and an organist from an early age.

Alexander Pott himself arranged Peter Warlock’s Folk Song Preludes of 1918, a set of five delightful miniatures. His notes identify the folk songs employed, except that the first has not been identified. My guess is that it is Scottish, like Nos 2, 3 and 5. The fourth embodies a Welsh tune; Warlock had strong connections with Wales, and learned the language. Pott refers to something that I had noticed independently: that Warlock’s characteristically whimsical direction to the pianist to make a crescendo and a diminuendo on the penultimate chord (bar 16) is something actually achievable on the organ!

My third choice is ‘The Immovable Do’ by Percy Grainger. (Grainger, like Warlock, was a friend of Delius, whose music and that of his circle is of great interest and importance to Pott ‘as a researcher on Delius’.) ‘Do’, the first note in the tonic solfa series can be movable, in that it will be the tonic in whatever key is in use. Its immobility in Grainger’s piece is explained by the subtitle ‘The Cyphering C’: the top C sounds throughout the piece, having been ‘wedged down with a pencil’ to imitate the familiar organ fault of a note getting stuck and persisting when not needed.

What does the composer do when incorporating a simulated cypher? He or she can employ harmonies that accord with the perpetual C, with minor licences, perhaps – as Purcell did in his ‘Fantazia on One Note, with its internal pedal-note F. Noel Rawsthorne (1929–2019), whose charming ‘Prière’ for organ has top C similarly wedged down throughout, is also generally ‘law-abiding’. Grainger, in a piece lasting 5’38”, is, as we might expect, harmonically more adventurous from time to time, although the basic F major tonality is emphasised. Grainger’s F major (like Rawsthorne’s) in fact means that the held C is the dominant (‘so’), rather than ‘do’. This is no doubt because overall the harmony is easier to manage this way (in C major there would be too many B-against-C clashes probably; in F a V–I progression will be entirely consonant).

Grainger’s piece is published, and an edition (from Schirmer) may be viewed in the online Petrucci Music Library. There is an extensive note there from the composer, explaining that the work was conceived in 1933, but not ‘written out’ for organ until 1941, although it was originally thought of as ‘for organ (or harmonium) or voices, or both together (with possible association of strings and wind groups, or orchestra, or band)’. Typical Grainger touches are the sometimes idiosyncratic English performance directions, including the opening ‘Stridingly’ – and the dedication ‘For my merry wife’.