In The Stillness – Review by Laudate Magazine

“Jervaulx Singers and their director are to be congratulated on a fine and enterprising selection of music for and about Christmas, excellently performed.”

12th September 2025

In The Stillness – Review by Laudate Magazine

“Jervaulx Singers and their director are to be congratulated on a fine and enterprising selection of music for and about Christmas, excellently performed.”

12th September 2025

Listen or buy this album:

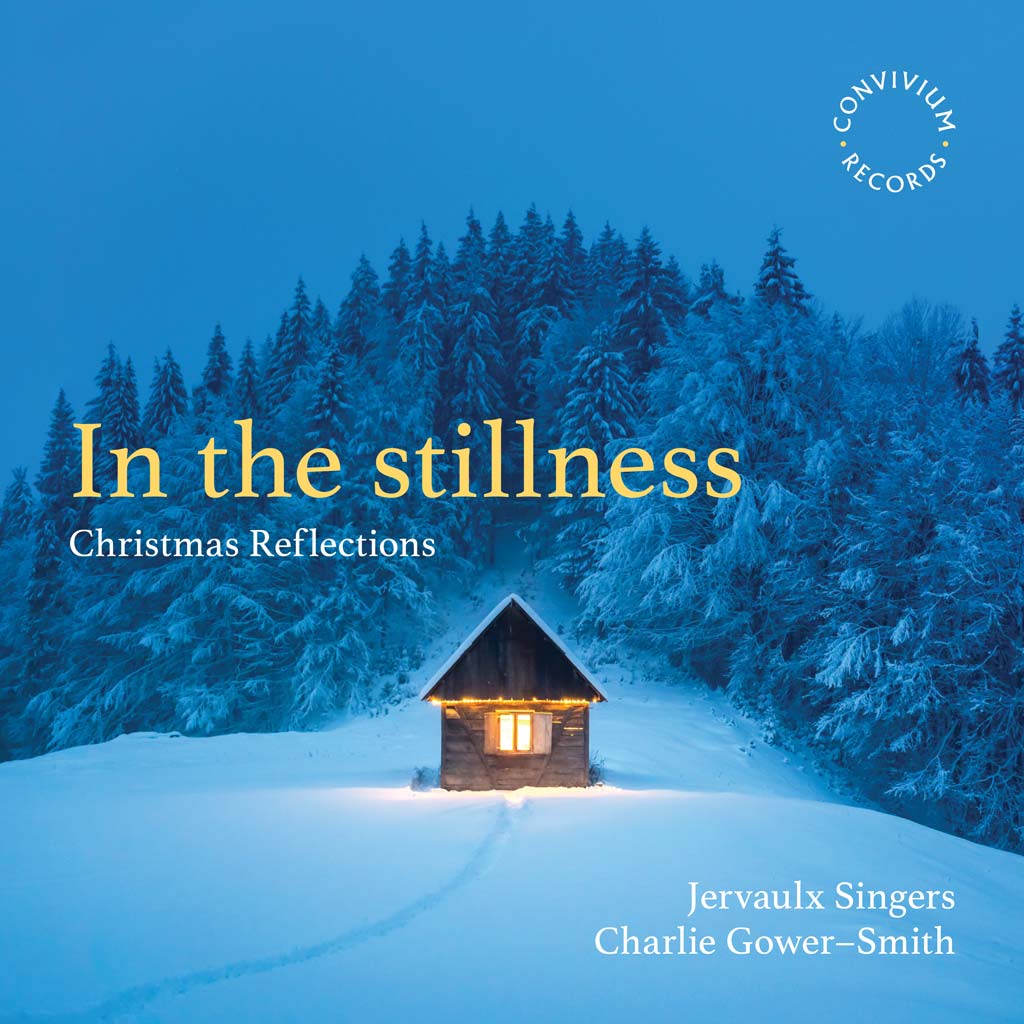

Jervaulx Singers and their director are to be congratulated on a fine and enterprising selection of music for and about Christmas, excellently performed. Perhaps this review is in time to influence decisions regarding Christmas services (although not every track would find a place there) – but it is certainly in time to suggest, for example, a possible gift for a music-loving friend or relative.

There are 18 pieces here, with an overall duration of 61 minutes. Thirteen are for unaccompanied voices; in the other five Alison Frances Gill supports with immaculate piano accompaniment. The eight singers, founded by Charlie Gower-Smith and one of the sopranos Jenny Bianco, are an outstanding choir of soloists, who enjoy combining choral music with song and opera in the creation of exciting and diverse programmes. Readers may recall the review of their previous Convivium CD (CR101 Les Chansons des Roses) in Laudate 115.

The present selection has an interesting mix of well-known and less widely known pieces, with some of the former re-arranged to suit the forces employed. ‘Nativity Carol’ (music and text by John Rutter), one of his earlier pieces is in its original form, with the piano accompaniment in line with the composer’s direction ‘piano or organ’. Reginald Jacques’s simple arrangement for four-part choir of ‘Away in a Manger’ appears as it is in, for example, Carols for Choirs 1. David Willcocks’s ‘Sing lullaby’ is included (Carols for Choirs 2) under the title ‘The Infant King’. Elizabeth Poston’s ‘Jesus Christ the apple tree’ is one of the highlights of this recording.

Attractive and imaginative new arrangements include ‘Silent Night’ (a cappella) by Darius Battiwalla, which, as it progresses, includes some luscious ‘jazzy’ harmonies, some perhaps tongue-in-cheek. Peter Cornelius’s ‘Die Könige’ appears in a version by Clytus Gottwald with the original German text, but without the celebrated tenor solo in Ivor Atkins’s arrangement (‘The Three Kings’).

Laurence Williams has made an ambitious arrangement of Adolphe Adam’s ‘Cantique de Noël’ which is the concluding – culminating – piece on this CD. As the programme note says, ‘Influences of both Mendelssohn and Rachmaninov pervade the accompaniment, whilst the choir writing is based on the double choir textures developed by Gabrieli and Schütz. The final cadence returns us to the stillness of Christmas’ after a powerful climax.

In the macaronic text of the ancient hymn ‘In dulci jubilo’ two languages are heard in alternation: Latin (‘In dulci jubilo’, ‘O Jesu parvule’, etc.) and German (‘Nunc singet und seid froh!’, etc.). Jervaulx Singers give us an interesting (or perhaps slightly curious!) combination of Michael Praetorius (1571–1621) for verse 1, J.S. Bach (1685–1750) for verse 2 – and then R.L. Pearsall’s arrangement of verses 3 and 4, with English and Latin alternating.

It is not surprising that some other familiar Christmas texts appear to new musical settings. Becky’s McGlade’s beautiful ‘In the bleak midwinter’ wisely sets verses 1, 2 and 5 of this long hymn text, in strophic fashion with a delightful summative extension of the final verse.

Medievalism is represented by Thomas Hewitt Jones’s ‘Lullay, my liking’ and Matthew Coleridge’s ‘Adam lay ybounden’. The former is very attractive melodically and harmonically, although arguably at five-and-a-half minutes a trifle over-long for some performance circumstances with the refrain repeated in full after every verse – but the piece would be ideal for ‘devotional listening’. Coleridge’s ‘Adam lay ybounden’, the most ‘modern’ sounding track on the CD, is well placed between Rutter’s ‘Nativity Carol’ and Jacques’s ‘Away in a manger’. There is quite a lot of verbal repetition in a manner which may recall some recent Baltic music, and this exploits well the alliterative b sounds in verse 1. Altogether the piece is placed deliberately worlds away from a setting such as Boris Ord’s.

The choice of other poetic texts is fresh and enterprising. The opening items are Bob Chilcott’s ‘The Shepherd’s Carol’ on a text by Clive Sansom (whose content is outlined in the programme note), and Richard Rodney Bennett’s ‘Pure nobis’ which has, despite the title, an entirely English text about the coming of the Christ Child by Alice Meynell (1847–1922). And the title track, ‘In the stillness’, is a very effective homophonic setting by Sally Beamish of a poem by Katrina Shepherd. John Hearne’s ‘There’s a song in the air’ sets a four-verse poem by the 19th-century American poet Josiah G. Holland. The first three verses are appropriately restrained, while the fourth (‘We rejoice in the light’) is more animated, almost ecstatic, the contrast arising partly from a much higher soprano part.

Three other pieces remain, all of great interest and not in the usual Nine Lessons and Carols province.

The one that appealed to me most was Debussy’s ‘Noël des enfants qui n’ont plus de maisons’, composed late in 1915, a year into World War One. The text is Debussy’s own, and it is partly a lament by children for the destruction of their homes (‘jusqu’à notre petit lit’ – ‘even our little bed’) and the burning of their school, and church (including an image of Christ – ‘monsieur Jésus-Christ’), with attendant fatalities. Papa is away at the war, and Maman is dead. The rest of the text is a call for vengeance – addressed to ‘Noël’ rather than to God (who is not mentioned) and ending (in translation) ‘Noël! Hear us…but give victory to the children of France’. The music is generally naïve (in the neutral sense of this word), as accords with the imagined voice(s) of the child(ren), and much of the accompaniment is simple and diatonic, although with constant quavers at dotted crotchet = 144 considerable dexterity is required. The song was originally a mélodie (the French parallel of the German Lied), for solo voice and piano. However, the Jervaulx Singers use Debussy’s chorus version (1916) for soprano and alto.

The soloist in Fauré’s mélodie ‘Noël’ (Op. 43 No. 1) is Gareth Meirion Edmunds (tenor) with piano. Victor Wilder’s text tells of the visit of ‘les mages’ with their gifts, to the infant Jesus, and adds an exhortation to us to ‘follow their devout example’. Voice and accompaniment are beautifully judged: the opening couplet has a shapely melody above a four-part piano texture (heard six times without change), with a syncopated inner part and appoggiaturas creating delicious harmonies (alternating in passing between chord I with a ninth and II6 with an eleventh above the bass).

Jervaulx Singers, as stated, enjoy combining choral music with song and opera in their programmes. We have seen songs from Fauré and Debussy; track 7 is the opening solo from Samuel Barber’s opera Vanessa, ‘Must the winter come so soon?’ (sung by mezzo soprano Beth Moxon). This is unconnected with the Nativity – but it fits well with the CD’s title In the Stillness: Christmas Reflections.

Review written by:

Review published in:

Other reviews by this author:

Featured artists:

Featured composers:

Jervaulx Singers and their director are to be congratulated on a fine and enterprising selection of music for and about Christmas, excellently performed. Perhaps this review is in time to influence decisions regarding Christmas services (although not every track would find a place there) – but it is certainly in time to suggest, for example, a possible gift for a music-loving friend or relative.

There are 18 pieces here, with an overall duration of 61 minutes. Thirteen are for unaccompanied voices; in the other five Alison Frances Gill supports with immaculate piano accompaniment. The eight singers, founded by Charlie Gower-Smith and one of the sopranos Jenny Bianco, are an outstanding choir of soloists, who enjoy combining choral music with song and opera in the creation of exciting and diverse programmes. Readers may recall the review of their previous Convivium CD (CR101 Les Chansons des Roses) in Laudate 115.

The present selection has an interesting mix of well-known and less widely known pieces, with some of the former re-arranged to suit the forces employed. ‘Nativity Carol’ (music and text by John Rutter), one of his earlier pieces is in its original form, with the piano accompaniment in line with the composer’s direction ‘piano or organ’. Reginald Jacques’s simple arrangement for four-part choir of ‘Away in a Manger’ appears as it is in, for example, Carols for Choirs 1. David Willcocks’s ‘Sing lullaby’ is included (Carols for Choirs 2) under the title ‘The Infant King’. Elizabeth Poston’s ‘Jesus Christ the apple tree’ is one of the highlights of this recording.

Attractive and imaginative new arrangements include ‘Silent Night’ (a cappella) by Darius Battiwalla, which, as it progresses, includes some luscious ‘jazzy’ harmonies, some perhaps tongue-in-cheek. Peter Cornelius’s ‘Die Könige’ appears in a version by Clytus Gottwald with the original German text, but without the celebrated tenor solo in Ivor Atkins’s arrangement (‘The Three Kings’).

Laurence Williams has made an ambitious arrangement of Adolphe Adam’s ‘Cantique de Noël’ which is the concluding – culminating – piece on this CD. As the programme note says, ‘Influences of both Mendelssohn and Rachmaninov pervade the accompaniment, whilst the choir writing is based on the double choir textures developed by Gabrieli and Schütz. The final cadence returns us to the stillness of Christmas’ after a powerful climax.

In the macaronic text of the ancient hymn ‘In dulci jubilo’ two languages are heard in alternation: Latin (‘In dulci jubilo’, ‘O Jesu parvule’, etc.) and German (‘Nunc singet und seid froh!’, etc.). Jervaulx Singers give us an interesting (or perhaps slightly curious!) combination of Michael Praetorius (1571–1621) for verse 1, J.S. Bach (1685–1750) for verse 2 – and then R.L. Pearsall’s arrangement of verses 3 and 4, with English and Latin alternating.

It is not surprising that some other familiar Christmas texts appear to new musical settings. Becky’s McGlade’s beautiful ‘In the bleak midwinter’ wisely sets verses 1, 2 and 5 of this long hymn text, in strophic fashion with a delightful summative extension of the final verse.

Medievalism is represented by Thomas Hewitt Jones’s ‘Lullay, my liking’ and Matthew Coleridge’s ‘Adam lay ybounden’. The former is very attractive melodically and harmonically, although arguably at five-and-a-half minutes a trifle over-long for some performance circumstances with the refrain repeated in full after every verse – but the piece would be ideal for ‘devotional listening’. Coleridge’s ‘Adam lay ybounden’, the most ‘modern’ sounding track on the CD, is well placed between Rutter’s ‘Nativity Carol’ and Jacques’s ‘Away in a manger’. There is quite a lot of verbal repetition in a manner which may recall some recent Baltic music, and this exploits well the alliterative b sounds in verse 1. Altogether the piece is placed deliberately worlds away from a setting such as Boris Ord’s.

The choice of other poetic texts is fresh and enterprising. The opening items are Bob Chilcott’s ‘The Shepherd’s Carol’ on a text by Clive Sansom (whose content is outlined in the programme note), and Richard Rodney Bennett’s ‘Pure nobis’ which has, despite the title, an entirely English text about the coming of the Christ Child by Alice Meynell (1847–1922). And the title track, ‘In the stillness’, is a very effective homophonic setting by Sally Beamish of a poem by Katrina Shepherd. John Hearne’s ‘There’s a song in the air’ sets a four-verse poem by the 19th-century American poet Josiah G. Holland. The first three verses are appropriately restrained, while the fourth (‘We rejoice in the light’) is more animated, almost ecstatic, the contrast arising partly from a much higher soprano part.

Three other pieces remain, all of great interest and not in the usual Nine Lessons and Carols province.

The one that appealed to me most was Debussy’s ‘Noël des enfants qui n’ont plus de maisons’, composed late in 1915, a year into World War One. The text is Debussy’s own, and it is partly a lament by children for the destruction of their homes (‘jusqu’à notre petit lit’ – ‘even our little bed’) and the burning of their school, and church (including an image of Christ – ‘monsieur Jésus-Christ’), with attendant fatalities. Papa is away at the war, and Maman is dead. The rest of the text is a call for vengeance – addressed to ‘Noël’ rather than to God (who is not mentioned) and ending (in translation) ‘Noël! Hear us…but give victory to the children of France’. The music is generally naïve (in the neutral sense of this word), as accords with the imagined voice(s) of the child(ren), and much of the accompaniment is simple and diatonic, although with constant quavers at dotted crotchet = 144 considerable dexterity is required. The song was originally a mélodie (the French parallel of the German Lied), for solo voice and piano. However, the Jervaulx Singers use Debussy’s chorus version (1916) for soprano and alto.

The soloist in Fauré’s mélodie ‘Noël’ (Op. 43 No. 1) is Gareth Meirion Edmunds (tenor) with piano. Victor Wilder’s text tells of the visit of ‘les mages’ with their gifts, to the infant Jesus, and adds an exhortation to us to ‘follow their devout example’. Voice and accompaniment are beautifully judged: the opening couplet has a shapely melody above a four-part piano texture (heard six times without change), with a syncopated inner part and appoggiaturas creating delicious harmonies (alternating in passing between chord I with a ninth and II6 with an eleventh above the bass).

Jervaulx Singers, as stated, enjoy combining choral music with song and opera in their programmes. We have seen songs from Fauré and Debussy; track 7 is the opening solo from Samuel Barber’s opera Vanessa, ‘Must the winter come so soon?’ (sung by mezzo soprano Beth Moxon). This is unconnected with the Nativity – but it fits well with the CD’s title In the Stillness: Christmas Reflections.